I am very grateful to my friend, Philip Dixon, for bringing this amazing sale to my attention. A very rare oak mount of the royal badge of Anne Boleyn almost certainly from Hampton Court Palace. It leads the Bonhams Oak Interior Sale at Bonhams Auctioneers, Oxford saleroom, on Wednesday 18 September, and is estimated at £50,000-80,000.

Excited, I rang Mr David Houlston, Head of Oak furniture at Bonhams, and he kindly agreed that I can use the catalogue information for this blog. So here is what he has to say about this spectacular piece:

A significant and rare Henry VIII carved oak mount, 1533-6, of Anne Boleyn's (c.1501-36) royal badge, possibly by Richard Rydge (fl. 1532-6)

Covered now in an off-black paint, with traces of a lighter pinkish bole below, and scattered areas of red pigment, and gilding, and modelled as a falcon wearing a closed imperial crown, its fore-wing furled over at the top, its rear wing aloft, and holding a sceptre formed as a pair of opposing balusters topped by a gadrooned ball knop, the falcon standing on a tapering stump or woodstock, pounced and with dentil-like protrusions, and issuing a spray of three rows of four flowers, on four curving stalks, 19.5cm wide x 3.5cm deep x 20.5cm high, (7 1/2in wide x 1in deep x 8in high)

Royal Badges at Hampton Court

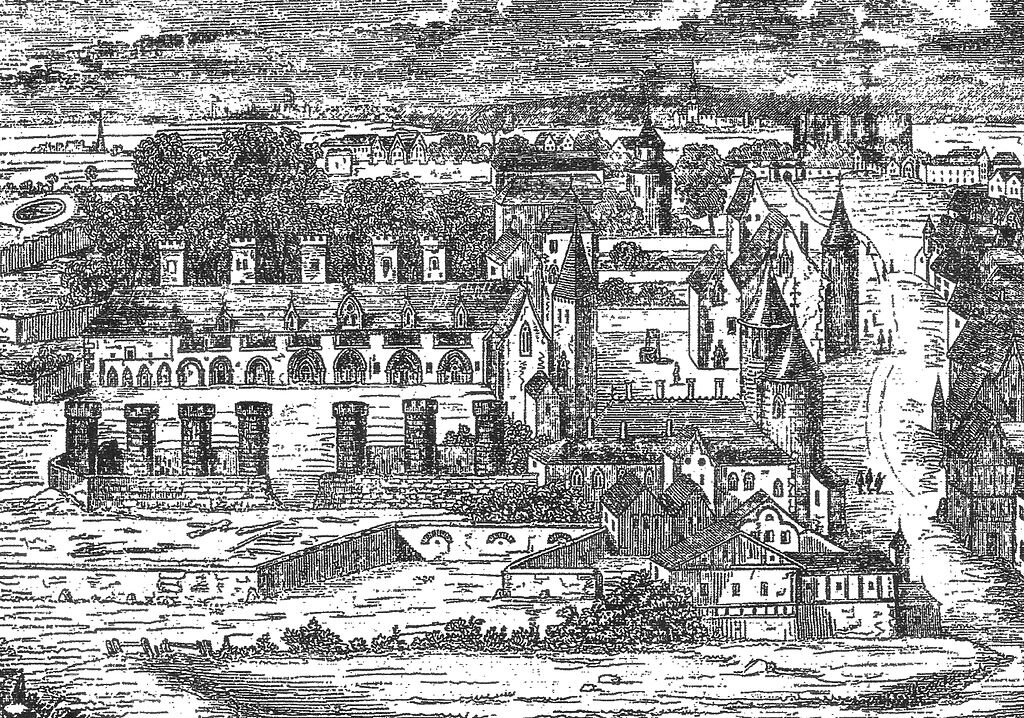

This badge's only known counterparts decorate the underside of the hammerbeam roof in the Great Hall at Hampton Court. Helpfully, given the inaccessibility of the ceiling and its ornaments, 60ft above the ground, the roof was surveyed by A. W. Pugin in the 1820s and his longitudinal drawing, published in Specimens of Gothic Architecture of 1821-3, was accompanied by detailed drawings of the roof's ornamental badges, pendants and corbels, including a falcon.

Sitting alongside other royal symbols – a fleur-de-lys, a rose, a portcullis – the falcons (how many there were of each type of badge is not specified) Pugin found on the roof in the 1820s are identical to this boss in all but one feature. The knop at the top of the falcon's sceptre in Pugin's survey appeared to be shaped like a lozenge, with a flattened top point, its lower section with a pronounced taper, whilst here it is a ball shape, with a band at its centre, and gadrooned. In all other particulars – the arc of the falcon's beak, the curve of the stalks supporting the flowers, and the angle of the scroll or furl to the top of the fore-wing, for instance – the likeness is pronounced. Crucially, Pugin's drawings record the badge's height as 8in, and its width as 7 1/2in, precisely conforming to the dimensions of this badge.

The Great Hall roof was installed as part of the second phase of Henry VIII's rebuilding work at Hampton Court, which he had acquired on Thomas Wolsey's (c. 1473-1530) fall: he took responsibility for building works there in September 1529. Shortly afterwards, in 1530, Henry paid for repaving work and for the setting up of 'tablets containing the King's arms' in the Great Hall, overtly asserting his ownership of the palace [Thurley (1988), p. 10], but this 'upgrade' was totally overridden by the decision, probably taken at the end of 1531, to build an entirely new structure. The result was the last and greatest of the medieval halls to be built in England, a consciously anachronistic building, already superannuated at the time of its construction, but intended to convey the ancient authority of royalty in England. Indeed, the hammerbeam roof was outdated in 1532, at a time when stuccoed, boarded or coffered ceilings were being installed in fashionable buildings, and some of its elements are purely ornamental, serving no structural purpose [Thurley (2003), p. 51].

These elements, however, allowed for a greater surface area on which to apply ornamental and heraldic bosses, pendants and badges, and Henry took full advantage. Extensive accounts survive for this phase of work, and – unusually for this period – we know the names of some of the workmen responsible for decorating the roof. Thus, in 1533, the London carver Richard Rydge was paid for work on 'xvi pendants standyng under the hammer beam in the kynges new hall' [Thurley (1988), pp. 10-11]. Another carver, John Wright, is also mentioned in connection with the applied decoration, and it may be that he and Rydge 'designed and applied the embellishments themselves'. Records suggest that it was being painted in 1534 [ibid., p. 11] – the badges were painted brilliant colours and gilded – although carpenters working on the roof were issued candles to facilitate overtime in anticipation of a visit from Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in December 1535 [ibid., pp. 57-8], so it is not clear when precisely the roof was finished.

However, given that the roof appears to have escaped the impulse to obliterate Anne's memory which followed her execution in May 1536, so that other badges bearing Anne's falcon survive there in situ, it is unlikely that this badge – albeit possibly carved by the same craftsman or men – was originally located on the roof of Hampton Court's Great Hall. It is possible, of course, that it was removed from the roof during one of several periods of restoration and repair (in 1834, 1855-6 and, most extensively, in the 1920s) – about half the ceiling of Wolsey's closet, for instance dates from 1961 – and not re-installed. It is more likely, however, on balance, that it was originally fixed elsewhere. Other rooms at Hampton Court (and in other palaces) were embellished with royal badges during Anne's lifetime, providing possible locations for the source of this badge. We know, for instance, that a slightly later phase of building which focused on the Queen's 'new lodgings' at Hampton Court entailed the creation of 'xxxv armes and badges of moulded work lyned with tymber in the roof of the chamber of presence or dining chamber' by German born Robert Shynck. He was a moulder, however, working in leather maché, moulding and pressing elements into shape, and so it is unlikely that this boss, being of oak, was part of that scheme. The example serves, however, to illustrate the fact that there must have been hundreds of royal badges in various parts of Hampton Court and in other royal palaces in the 1530s.

If originally from Hampton Court, the most likely place that this badge may have sat is the screen, fitted in the lower end of the Great Hall at around the same time as the rest of the woodwork in the room was installed. Indeed, we know that Rydge worked on both the screen and the roof, being paid '2s. 6d. the peece' for 'cutting and carving of 32 lintels, wrought with King's badges and the Queene's standing in the screens within the Kings new hall' [Law (188), p. 170]. Made by some of the same craftsmen, and part of the same phase of work for the same room, it is likely that the screen's badges would have complimented – matched, even – those of the roof. These lintels have now disappeared, and they and their badges seem to have been removed sometime before 1821, when the screen was drawn by Thomas Hardwick (1752-1829), then clerk of works at Hampton Court (http://collections.soane.org/THES100339).

Anne Boleyn (c. 1501 – May 1536), and her badge

This work at Hampton Court coincided with, and was probably a direct result of, the development of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII's relationship, when their secret betrothal in the summer of 1527 [Ives (2004), p. 90] and the tortuous and complex years which followed, culminated in their equally secret marriage (because Anne was by that time pregnant with their daughter, Elizabeth) in January 1533.

The badge that Anne adopted – or was granted –on this occasion heralded the start of a new and fertile phase of the Tudor dynasty. The falcon crowned and holding a sceptre, alighting on a woodstock (stump) issuing roses was a potent one, laden with royal and religious significance. Roses were emblematic of fertility and, being both red and white, represented the union of the Lancastrian and Yorkist claims to the English throne by the marriage of Henry's parents, Henry VII (d. 1509) and Elizabeth or York (d. 1503). The tree-stump or woodstock was a centuries old royal badge. The crown is Imperial, not kingly, a deliberate allusion to Henry's recent claims – as part of the 'Break with Rome' – to imperial power and so to the rejection of papal authority.

Albeit the falcon badge, in a simpler form devoid of royal regalia, is often referred to as the 'Boleyn falcon', it is not known to have been used by her immediate family before January 1533. Received understanding labels Anne 'low-born' but she was, as a recent biographer has pointed out, the most aristocratic of Henry's three English queens. Her mother was the daughter of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk and Surrey (d. 1524) and her father's mother was daughter and co-heir of Thomas Butler, earl of Ormonde (d. 1515). It was from the Butler earls of Ormonde that the falcon badge ultimately derived, a title only officially acquired by Anne's father – after a legal wrangle of fourteen years – in December 1529. Surviving evidence suggests that the first official use of this badge in connection with Anne was in the letters patent [British Library MS Harleian M303] confirming her elevation to the peerage as Marquis of Pembroke in her own right (September 1532), which were in fact drawn up and issued after the marriage ceremony in January 1533 [ibid., pp. 220-1 and p. 398].

Her association with the falcon was quickly established and, on the first day of her coronation celebrations on 29 May 1533, her white falcon appeared 'on a wherry' on the river, 'surrounded by virgins singing and playing sweetly'. Famously, the mechanical device which she encountered on her route through London comprised a stump which opened to pour out a mass of red and white roses, and a white falcon stooped to settle on the flowers. To complete the tableau, an angel descended from clouds and placed an imperial crown on the falcon's head.

We know of some objects from her lifetime that featured her falcon. An inventory of 1550, for instance, records that three gold spoons – one topped by a crowned falcon – and a laver with 'a falcon in the top', survived amongst the royal plate [Ives (2004), p. 232-3], and a cup at John the Baptist's Church at Cirencester, known as the Boleyn Cup, is topped by a falcon knop.

The true number of objects bearing her emblem is entirely obscured by the deliberate obliteration of any memory of her after she was executed in May 1536. For, just as Henry replaced Wolsey's badges at Hampton Court with his own in 1529, and just as Anne removed references to Katherine of Aragon (she employed glaziers to replace window glass in her Hampton Court lodgings in June 1529) so too were visual reminders of Anne eradicated from royal palaces. Thus, an enormous bill for painting of August/September 1536, just three to four months after Anne's execution, suggests a whole-sale re-decoration of Hampton Court's interiors, some of which took place in the hall and the queen's lodgings which were, in fact, extensively re-modelled. The King's Beasts carved by Henry Corant and Richard Rydge in 1535/6, were modified, and Anne's leopard (her secondary badge) was converted into Jane Seymour's panther [Thurley (2003), p. 60]. Substantial alteration of the interiors of the royal lodgings is also thought to have taken place in 1543, when apartments were prepared for Princess Mary and Katherine Parr.

The badges, ciphers and arms on the roof of the Great Hall are, because of this destructive impulse, a rare survival, a circumstance compounded by the fact that this badge - a royal one - was relevant during a relatively short period of only three years and five months. Reminders of her, however, survive elsewhere in situ, for instance, in ciphers on the screen in the chapel of King's College, Cambridge, and in the Gatehouse at St. James' largely, it is felt, because such important, beautiful (and occasionally inaccessible) structures were too important to deface. It is, perhaps, significant that it is her badge – rather than the badges of any of her successors as queen – which are associated with the most celebrated buildings and interiors of the Henrician period.

Poignantly, her badge was revived by her daughter, Elizabeth I. In no position to publicly commemorate her disgraced mother until her own accession to the throne in November 1558, the emblem is found in some of her books, and decorates the virginals in the Victoria & Albert Museum (Museum Number 19-1887), traditionally said to be Elizabeth's, made as late as 1594, and thus commemorating Anne almost sixty years after her death.

Select Literature:

E. Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (2004); S. Thurley, 'Henry VIII and the Building of Hampton Court: A Reconstruction of the Tudor Palace', in Architectural History, Vol. 31 (1998), 1 – 57; S. Thurley, Hampton Court: A Social and Architectural History (2003); Liam E. Semler, The Early Modern Grotesque: English Sources and Documents 1500-1700 (2019); E. Law, The History of Hampton Court Palace in Tudor Times (1885)